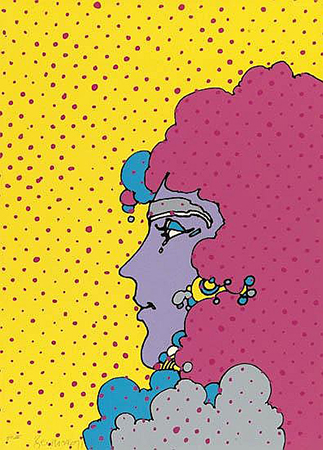

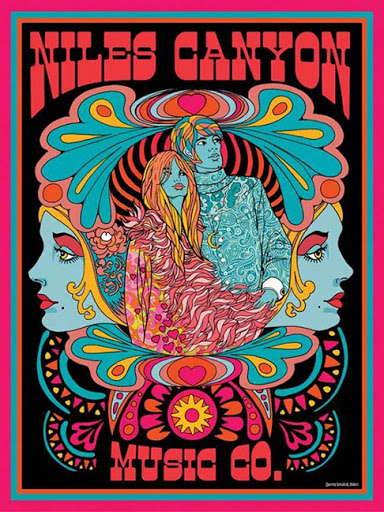

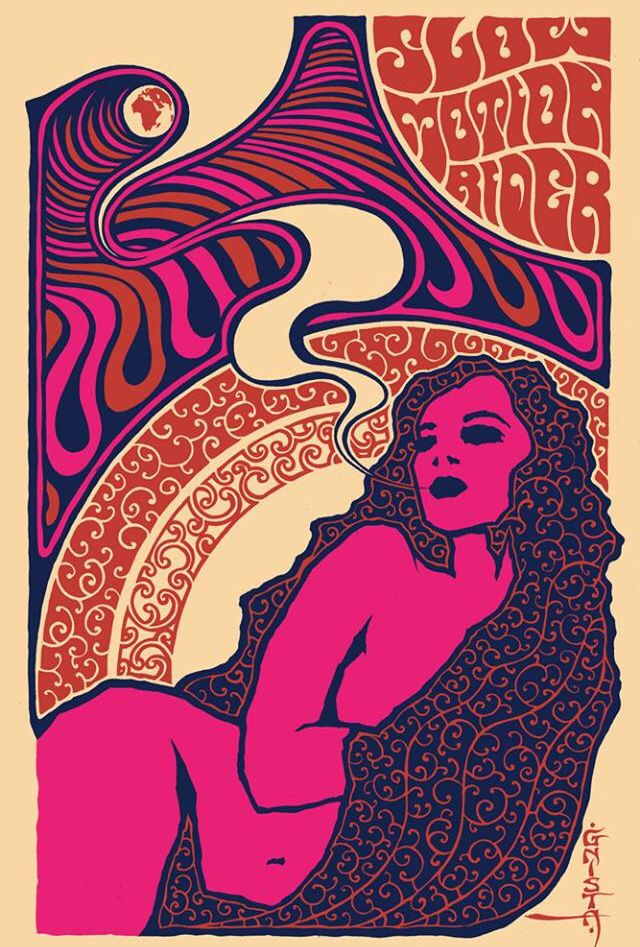

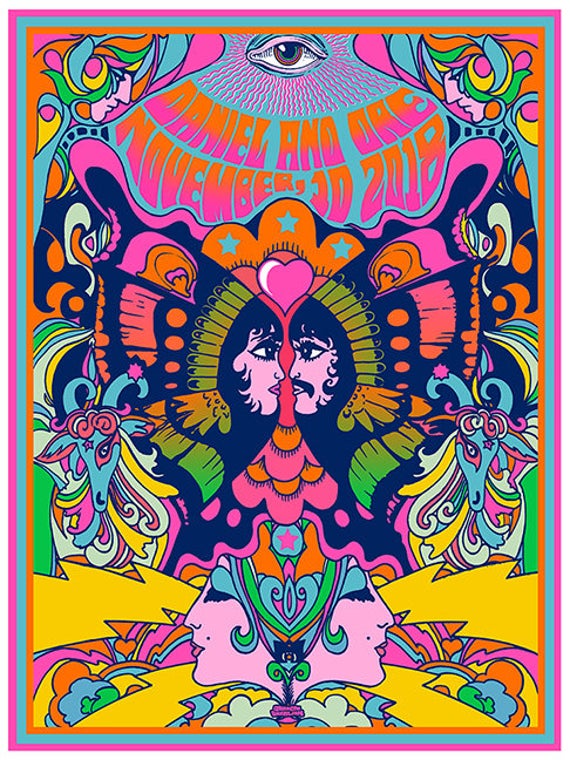

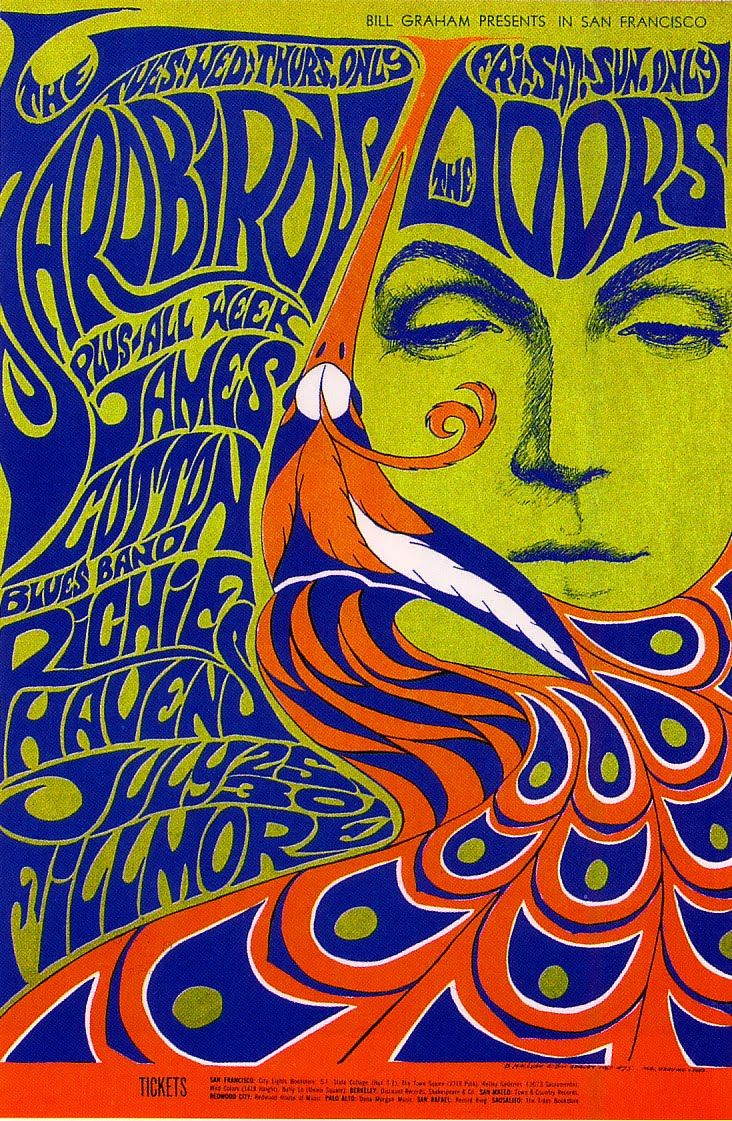

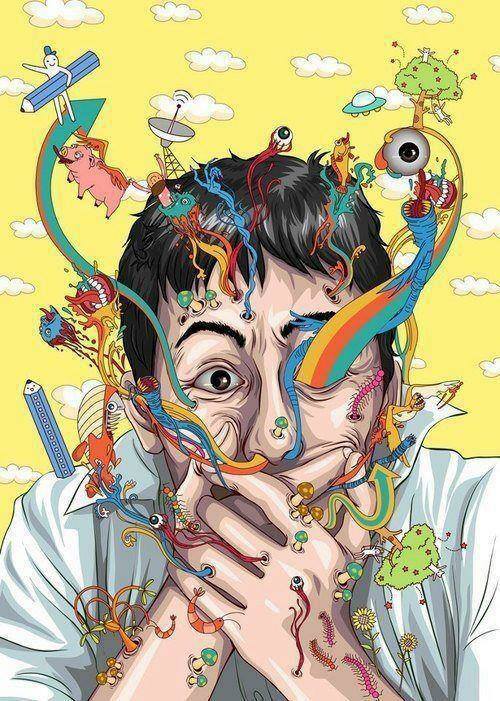

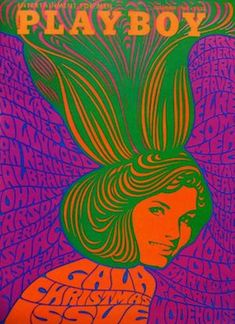

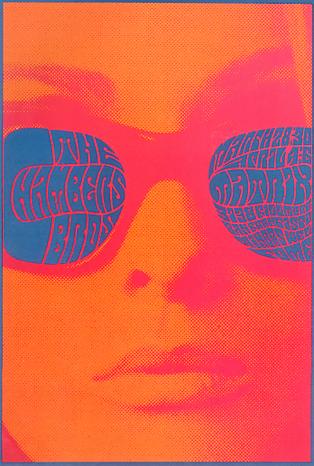

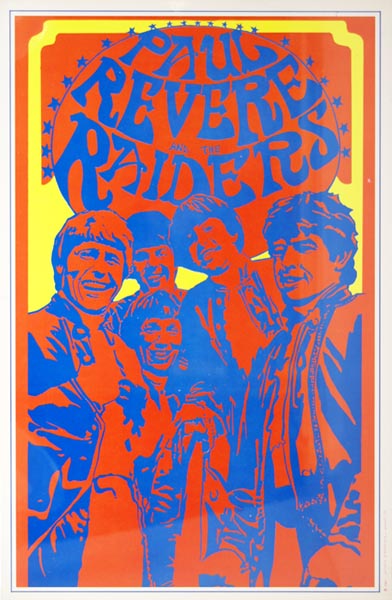

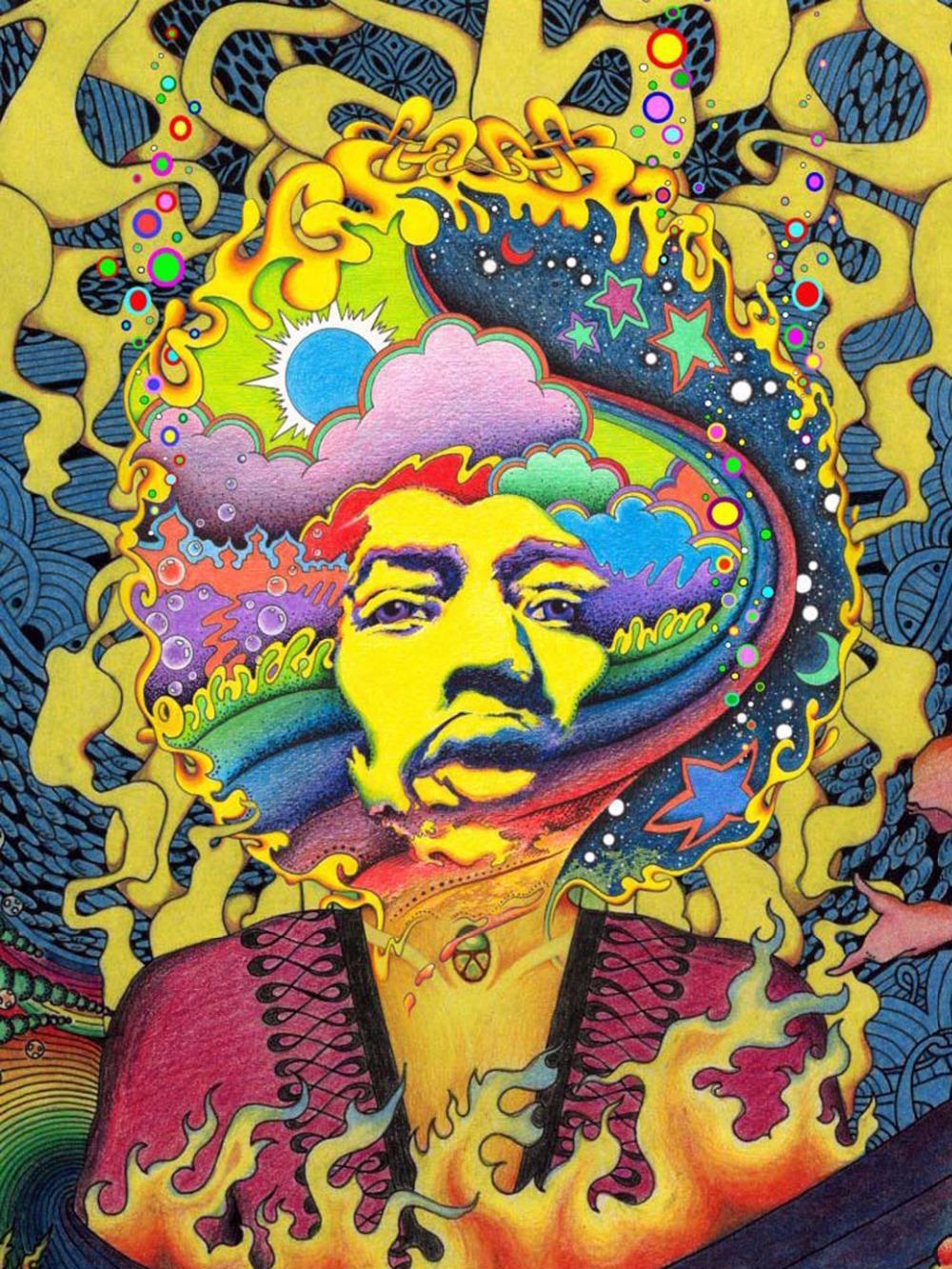

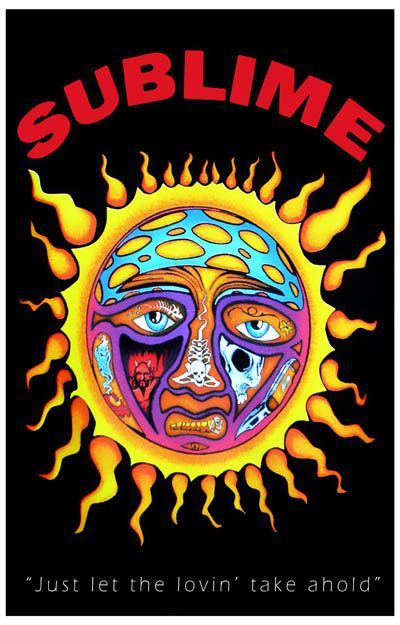

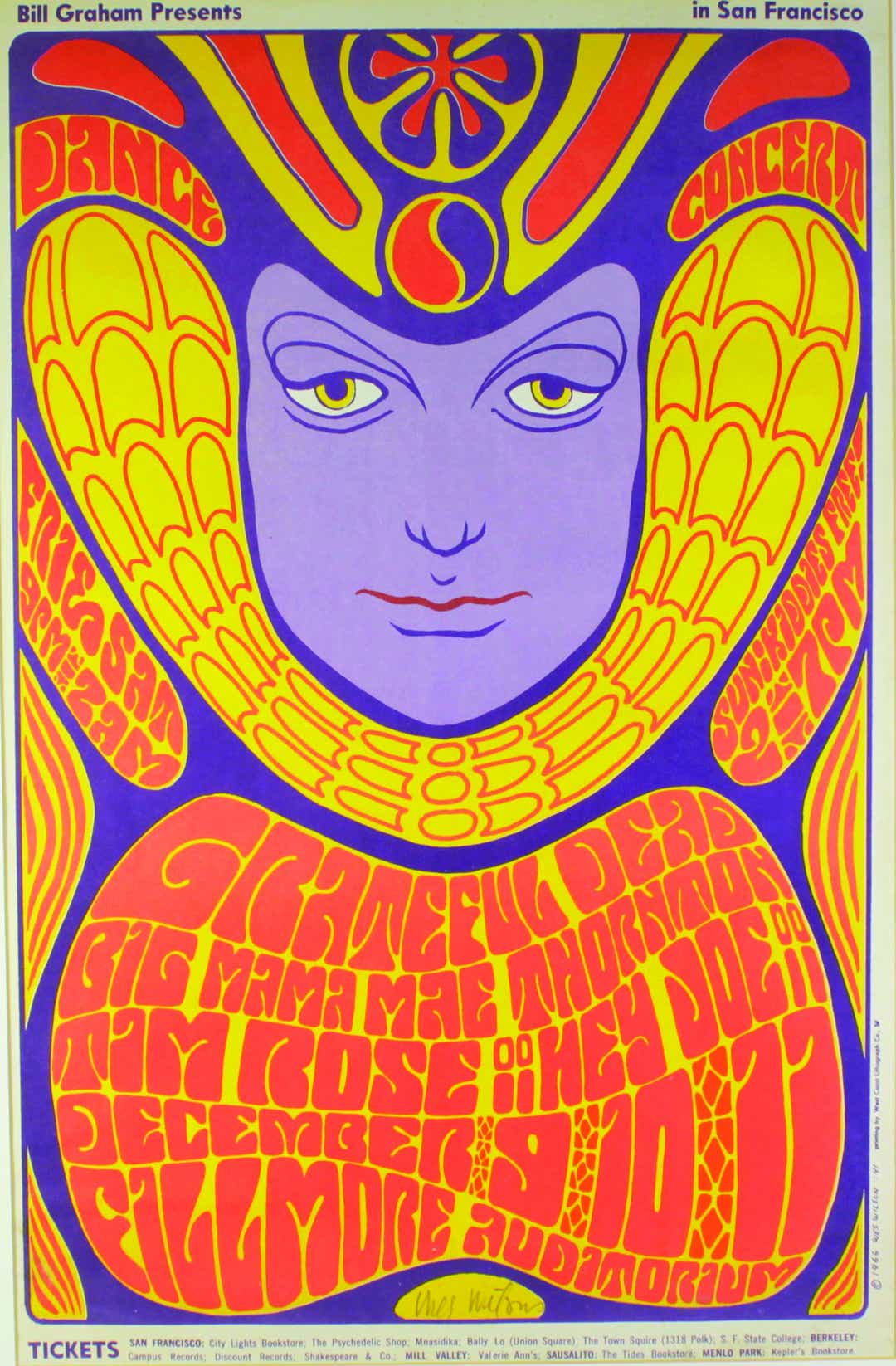

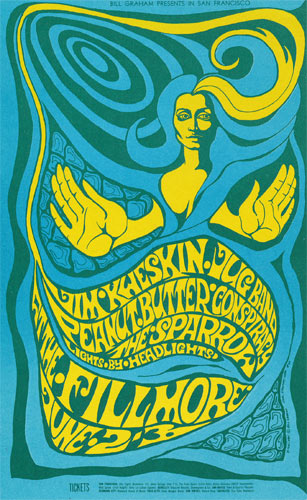

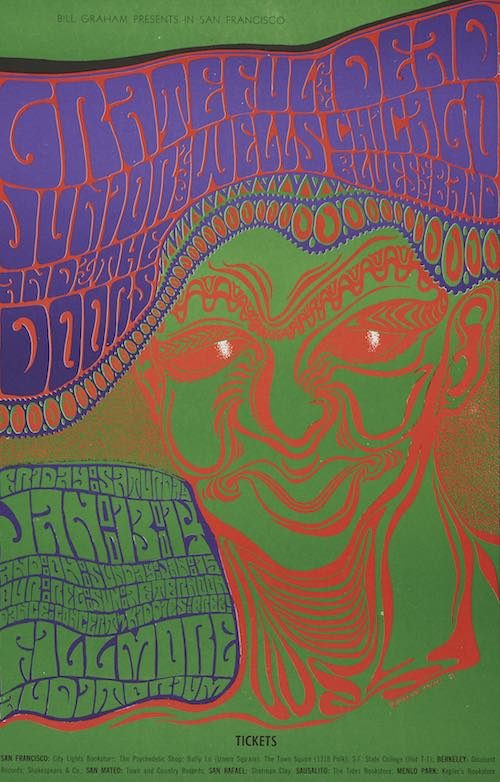

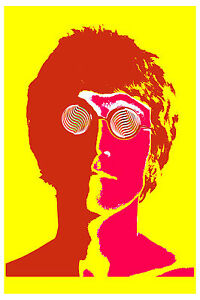

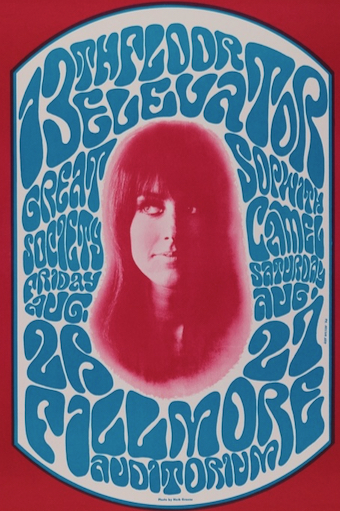

San Francisco in the 1960s was the world capital of counterculture mind expansion, where LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) was the rocket to an unexplored universe of perception and aesthetics. The word psychedelic, a meld of the Greek psyche and delos, meaning mind- or soul-manifesting, was promoted by a pantheon of passionate scientists, scholars and thinkers such as Timothy Leary, Ken Kesey and Oswald Stanley. (Even the film icon Cary Grant used “therapeutic” hallucinogens.) They made LSD’s very existence define the time and place. Yet before San Francisco exploded with flower power, hippie culture, white rabbits and psychedelic art, the drug had a more nefarious role in the early 20th century’s plunge into mass manipulation. Nazi scientists were among the first to explore LSD’s psychopharmaceutical potential, followed by international drug companies and ultimately the U.S. government. Altering consciousness for opportunistic outcomes, LSD, psilocybin and other psychedelic compounds were tested to determine how they could be employed as neuro-medical-military weapons, including how soldiers on the battlefield would perform while in altered states of mind. In 1938 the Swiss chemist Dr. Albert Hofmann was among the first to synthesize LSD into usable dosages, but even he didn’t realize its hallucinogenic properties until 1943. LSD was linked to the fate of the free world, when during the postwar years, the U.S. Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency in Europe launched Operation Paperclip, collaborating with former Nazi chemists led by Nobel Prize winner Richard Kuhn, who realized the power LSD could have in the interrogation of Soviet spies. Testing increased and it became a tool of counter-espionage. Arguably, this is when the LSD genie escaped its bottle and fled into the mainstream. In 1960, the gurus of acid, Harvard professors Leary and Richard Alpert (known as Ram Dass), started the Harvard Psilocybin Project initially to address how the so-called “magic mushrooms” they had discovered in Mexico altered the course of human conscious and subconscious behaviors. Serious studies and papers began to appear in scholarly journals, notably the Psychedelic Review (1963–1971), by researchers and creatives interested in everything from the religious to the neuropharmaceutical to the artistic potential of the drug.But for those unfamiliar with the history, psychedelics seemed to have emerged fully formed—the public opened their eyes one day, and San Francisco was suddenly awash with split fountain colors and illegible lettering on rock posters and San Francisco Oracle covers. Indeed, artists like Victor Moscoso, Mouse Studios, Wes Wilson, Rick Griffin and others integrated, reinterpreted and invented new undulating graphic languages that were partly influenced by the hallucinogens they imbued. But their work also defined the essence of psychedelic art and design. More than the inner eye, the outer view—and cultural code—was what categorized and embodied the experience and continues to do so. Indian music is not necessarily what is heard while tripping, but its ethereal quality was adopted as the sound of psychedelics. There are many ways to hallucinate, but to suggest an acid trip, filmmakers used gauze on their lenses. Fashion designers took vintage clothes, added outrageously decorative and colorful eff ects, and it became the style of the times.